Ochre

Ochre has ongoing importance to many Aboriginal people; it has religious significance and is used in ceremonies, healing practices and art. It has been used in rituals for at least 42,000 years; when the Aboriginal man known as ‘Mungo Man’ was buried he was covered in ochre, as part of a ritual burial. The ochre had come from more than 200km away.

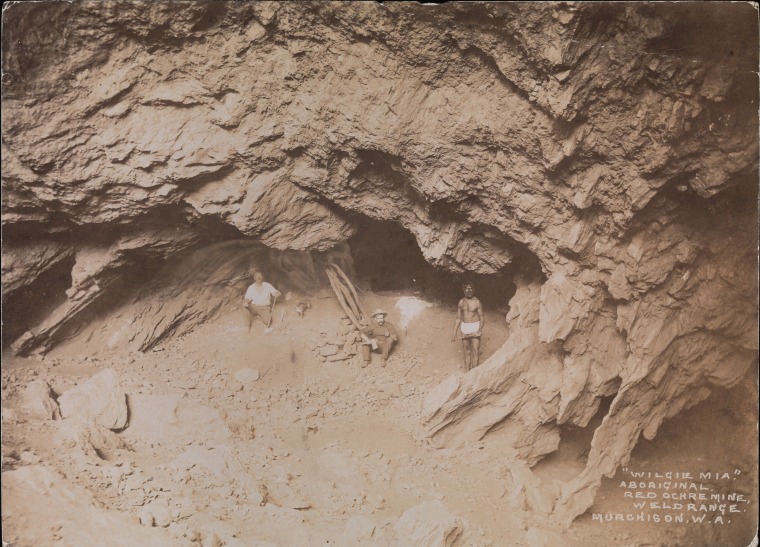

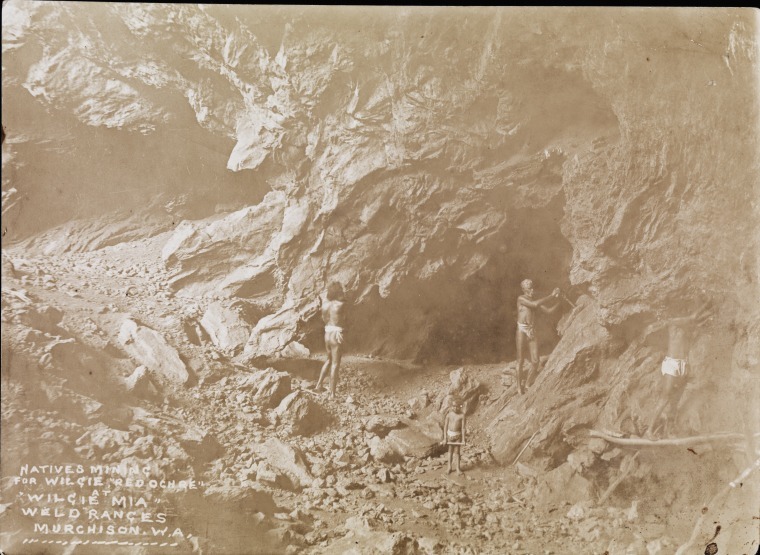

Wilgie Mia, or Thuwarri Thaa (the place of red ochre), is located in the Weld Ranges, Western Australia and is a significant ochre mine. Estimated to be 27,000 years old, it is believed to be the oldest continually worked mine site in human history. The ochre is very high quality and was an important part of pre-colonisation Aboriginal economies, being traded as far as Ravensthorpe, Queensland and the Nullarbor Plains in South Australia.

Wilgie Mia is also the largest and deepest underground Aboriginal ochre mine in Australia. Initiated Wajarri Yamatji men mined the ochre using heavy stone mauls and fire-hardened wooden wedges to pry away ochrous rock, which was then further broken up to separate the ochre. The pigment was then pulverised with rounded stones, dampened with water, and worked in to balls. The men used pole scaffolding and wooden platforms so they could simultaneously mine at different heights, increasing output. It is estimated that over 40,000 tonnes of rock and ochre were removed using this technique.

Wilgie Mia and its surrounding area, including Little Wilgie Mia and the Marlu Resting Place, are of great and ongoing cultural significance and sacredness to the Wajarri Yamatji people and neighbouring Aboriginal people. According to Colin Hamlett, the creation story goes:

A [red] Kangaroo [(Marlu)] was wounded down near the coast. It hopped back through the country and dropped spots of blood along the way. It dropped quite a bit at Little Wilgie Mia, then it died at Wilgie Mia which left a lot of ochre. Then the spirit of the Kangaroo moved from Wilgie Mia to the hill right next-door to it.

(Yamatji Marlpa Aboriginal Corporation, media release: 25 February 2011)

The traditional story also accounts for the different coloured ochres found in the area. They are all related to the different parts of Marlu’s body: the red ochre is his blood, the yellow ochre is his liver and green ochre is his gall.

In the 1940s, ochre was mined commercially by non-Aboriginal people - J. C. Zadow and J. G. Cassidy. The permit was later transferred to Universal Mining Company and then revoked because of illegal use of explosives and non-compliance with heritage-protection requirements. In 1973, following the introduction of the Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972, Wilgie Mia was declared a protected site. By then, however, 10,245 tonnes of ochre had been removed.

The company Weld Range Metals has owned four tenements surrounding the heritage site since 1986. They intended to start mining in the Weld Ranges but their application was rejected by the Native Title Tribunal in 2011. The rejection came after Weld Range Metals made limited attempts to work and negotiate with the Traditional Owners. As noted by Colin Hamlett:

"Aboriginal people aren't opposed to mining, but they do want to preserve certain areas, if the company just came to the table, we could have talked about it and preserved different areas… we're just trying to keep a little bit of our culture that belongs to us originally and to preserve it for generations to understand about Aboriginal culture." (The world’s oldest Aboriginal ochre mine is under dispute, ABC, 31 October 2011)

In October 2017 and April 2018 the Wajarri Yamajti people were successful in a two part Native Title determination. The second part included the Weld Ranges and Wilgie Mia and gave the Wajarri Yamatji people exclusive possession native title of the area. This means that the Wajarri Yamatji people have the right of possession, occupation, use, and enjoyment of these areas to the exclusion of all others.